10.50 + 9.25[1] 19.8This chapter introduces you to the technology we will use throughout the book. By technology, we mean three things:

In this chapter, we concentrate on the technology we use for the interactive version of the book. The interactive version allows you to run R code as interactive notebooks in your web browser.

Either now, or later, you should also consider running the code on your own computer — see Section 4.9.

The chapter introduces the R language, and then gives an example to introduce R and the RStudio Notebook. If you have not used R before, the example notebook will get you started. The example also shows how we will be using notebooks through the rest of the book.

This version of the book uses the R programming language to implement resampling algorithms.

The current title of the main website for R1 is “The R Project for Statistical Computing”, and this is a good summary of how R started, and what R is particularly good at. The people who designed R designed it for themselves, and you and I — those of us who are working to find and understand the patterns in data. Over the last 20 years, it has gained wide use for data analysis across many fields, especially in life sciences, data science and statistics.

Although many people use R as a simple way of exploring data and doing standard statistical tests, it is a full-fledged programming language.

It is crucial to our purpose that R is a programming language and not a set of canned routines for “doing statistics”. It means that we can explore the ideas of probability and statistics using the language of R to express those ideas. It also means that you, and we, and anyone else in the world, can write new code to share with others, so they can use our work, understand it, and improve it. This book is one example; we have written the R code in this book as clearly as we can to make it easy to follow, and to explain the underlying ideas. We hope you will help us by testing what we have done and sending us suggestions for ways we could improve. Please see Section 6 for more information about how to do that.

Many of the chapters have sections with code for you to run, and experiment with. These sections contain Jupyter notebooks. Jupyter notebooks are interactive web pages that allow you to read, write and run R code. We mark the start of each notebook in the text with a note-and-link heading like the one you see below. In the web edition of this book, you can click on the Download link in this heading to download the section as a notebook. You can also click on the Interact link to open the notebook in your web browser, using a system called JupyterLite. JupyterLite allows you to run the code in your browser, and experiment by making changes.

JupyterLite2 is a version of the Jupyter notebook and R that will automatically download and run inside your web browser.

When you click on the “Interact” link, it will take you to a web address that has the effect of making your browser download the JupyterLite system, along with a compatible version of the R language. The web page that opens allows you run to the R code in the notebook inside your browser.

In the print version of the book, we point you to the web version to get the “Download” and “Interact” links.

At the end of this chapter, we explain how to run these notebooks on your own computer. In the next section you will see an example notebook; to start with, you might want to run this in your browser using the “Interact” link.

The next section contains a notebook called “Billie’s Bill”. If you are looking at the web edition, you will see links to interact with this notebook in your browser, or download it to your computer.

The text in this notebook section assumes you have opened the page as an interactive notebook on the web. In that case, you are running the notebook in a version of Jupyter. We assume you are using Jupyter in the description that follows. You can also run R in Jupyter on your own computer, but we suggest that you do not do that. Instead, we recommend you use RStudio to work with R notebook files on your computer (see Section 4.9). The procedure for working with notebooks in RStudio is not the same as that for Jupyter. We give a short tutorial on using RStudio in another notebook after this one (see Section 4.9.2).

A notebook can contain blocks of text — like this one — as well as code, and the results from running the code.

Jupyter Notebooks are made up of cells.

As we said above, we assume you are running this notebook via the interactive web pages, and therefore, that you are running the notebook with Jupyter, not RStudio.

RStudio differs a little from Jupyter, because it does not have the idea of a text “cell” — instead it distinguishes between the main body of the notebook, made up of text, and code chunks — delimited sections in the notebook that contain code, instead of text. Jupyter would refer to these code chunks as code cells. We will go into more detail in Section 4.9.2.

Jupyter cells can contain text or code.

Notebook text can have formatting, such as links.

For example, this sentence ends with a link to the earlier second edition of this book.

If you are in the interactive notebook interface (rather than reading this in the textbook), you will see the Jupyter menu bar near the top of the page, with headings “File”, “Edit” and so on.

In Jupyter, underneath the File … menu bar, by default, you may see a row of icons - the “Toolbar”.

In the Jupyter toolbar, you may see icons to run the current cell, among others.

To move from one cell to the next, you can click the run icon in the toolbar, but it is more efficient to press the Shift key, and press Enter (with Shift still held down). Your keyboard may label the Enter key as “Return”. We will write this as Ctl/Cmd-Shift-Enter.

In this, our first notebook, we will be using R to solve one of those difficult and troubling problems in life — working out the bill in a restaurant.

Alex and Billie are at a restaurant, getting ready to order. They do not have much money, so they are calculating the expected bill before they order.

Alex is thinking of having the fish for £10.50, and Billie is leaning towards the chicken, at £9.25. First they calculate their combined bill.

Below this text you see a code chunk. It contains the R code to calculate the total bill. Press Control-Shift-Enter or Cmd-Shift-Enter (on Mac) in the chunk below, to see the total.(Remember, this is what you should do when running the code in Jupyter, via the interactive web pages. If you are using RStudio on your own computer, you should use different commands — see Section 4.9.2.).

10.50 + 9.25[1] 19.8The contents of the chunk above is R code. As you would predict, R understands numbers like 10.50, and it understands + between the numbers as an instruction to add the numbers.

When you press Ctl/Cmd-Shift-Enter, R finds 10.50, realizes it is a number, and stores that number somewhere in memory. It does the same thing for 9.25, and then it runs the addition operation on these two numbers in memory, which gives the number 19.75.

Finally, R sends the resulting number (19.75) back to the notebook for display. The notebook detects that R sent back a value, and shows it to us.

This is exactly what a calculator would do.

Let us continue with the struggle that Alex and Billie are having with their bill.

They realize that they will also need to pay a tip.

They think it would be reasonable to leave a 15% tip. Now they need to multiply their total bill by 0.15, to get the tip. The bill is about £20, so they know that the tip will be about £3.

In R * means multiplication. This is the equivalent of the “×” key on a calculator.

What about this, for the correct calculation?

# The tip - with a nasty mistake.

10.50 + 9.25 * 0.15[1] 11.9Oh dear, no, that isn’t doing the right calculation.

R follows the normal rules of precedence with calculations. These rules tell us to do multiplication before addition.

See https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Order_of_operations for more detail on the standard rules.

In the case above, the rules tell R to first calculate 9.25 * 0.15 (to get 1.3875) and then to add the result to 10.50, giving 11.8875.

We need to tell R we want it to do the addition and then the multiplication. We do this with round brackets (parentheses):

There are three types of brackets in R.

These are:

();[];{}.Each type of bracket has a different meaning in R. In the examples, play close to attention to the type of brackets we are using.

# The bill plus tip - mistake fixed.

(10.50 + 9.25) * 0.15[1] 2.96The obvious next step is to calculate the bill including the tip.

# The bill, including the tip

10.50 + 9.25 + (10.50 + 9.25) * 0.15[1] 22.7At this stage we start to feel that we are doing too much typing. Notice that we had to type out 10.50 + 9.25 twice there. That is a little boring, but it also makes it easier to make mistakes. The more we have to type, the greater the chance we have to make a mistake.

To make things simpler, we would like to be able to store the result of the calculation 10.50 + 9.25, and then re-use this value, to calculate the tip.

This is the role of variables. A variable is a value with a name.

Here is a variable:

# The cost of Alex's meal.

a <- 10.50a is a name we give to the value 10.50. You can read the line above as “The variable a gets the value 10.50”. We can also talk of setting the variable. Here we are setting a to equal 10.50.

Now, when we use a in code, it refers to the value we gave it. For example, we can put a on a line on its own, and R will show us the value of a:

# The value of a

a[1] 10.5We did not have to use the name a — we can choose almost any name we like. For example, we could have chosen alex_meal instead:

# The cost of Alex's meal.

# alex_meal gets the value 10.50

alex_meal <- 10.50We often set variables like this, and then display the result, all in the same chunk. We do this by first setting the variable, as above, and then, on the final line of the chunk, we put the variable name on a line on its own, to ask R to show us the value of the variable. Here we set billie_meal to have the value 9.25, and then show the value of billie_meal, all in the same chunk.

# The cost of Alex's meal.

# billie_meal gets the value 10.50

billie_meal <- 10.50

# Show the value of billie_meal

billie_meal[1] 10.5Of course, here, we did not learn much, but we often set variable values with the results of a calculation. For example:

# The cost of both meals, before tip.

bill_before_tip <- 10.50 + 9.25

# Show the value of both meals.

bill_before_tip[1] 19.8But wait — we can do better than typing in the calculation like this. We can use the values of our variables, instead of typing in the values again.

# The cost of both meals, before tip, using variables.

bill_before_tip <- alex_meal + billie_meal

# Show the value of both meals.

bill_before_tip[1] 21We make the calculation clearer by writing the calculation this way — we are calculating the bill before the tip by adding the cost of Alex’s and Billie’s meal — and that’s what the code looks like. But this also allows us to change the variable value, and recalculate. For example, say Alex decided to go for the hummus plate, at £7.75. Now we can tell R that we want alex_meal to have the value 7.75 instead of 10.50:

# The new cost of Alex's meal.

# alex_meal gets the value 7.75

alex_meal = 7.75

# Show the value of alex_meal

alex_meal[1] 7.75Notice that alex_meal now has a new value. It was 10.50, but now it is 7.75. We have reset the value of alex_meal. In order to use the new value for alex_meal, we must recalculate the bill before tip with exactly the same code as before:

# The new cost of both meals, before tip.

bill_before_tip <- alex_meal + billie_meal

# Show the value of both meals.

bill_before_tip[1] 18.2Notice that, now we have rerun this calculation, we have reset the value for bill_before_tip to the correct value corresponding to the new value for alex_meal.

All that remains is to recalculate the bill plus tip, using the new value for the variable:

# The cost of both meals, after tip.

bill_after_tip = bill_before_tip + bill_before_tip * 0.15

# Show the value of both meals, after tip.

bill_after_tip[1] 21Now we are using variables with relevant names, the calculation looks right to our eye. The code expresses the calculation as we mean it: the bill after tip is equal to the bill before the tip, plus the bill before the tip times 0.15.

Now you have done some practice with the notebook, and with variables, you are ready for a new problem in probability and statistics, in the next chapter.

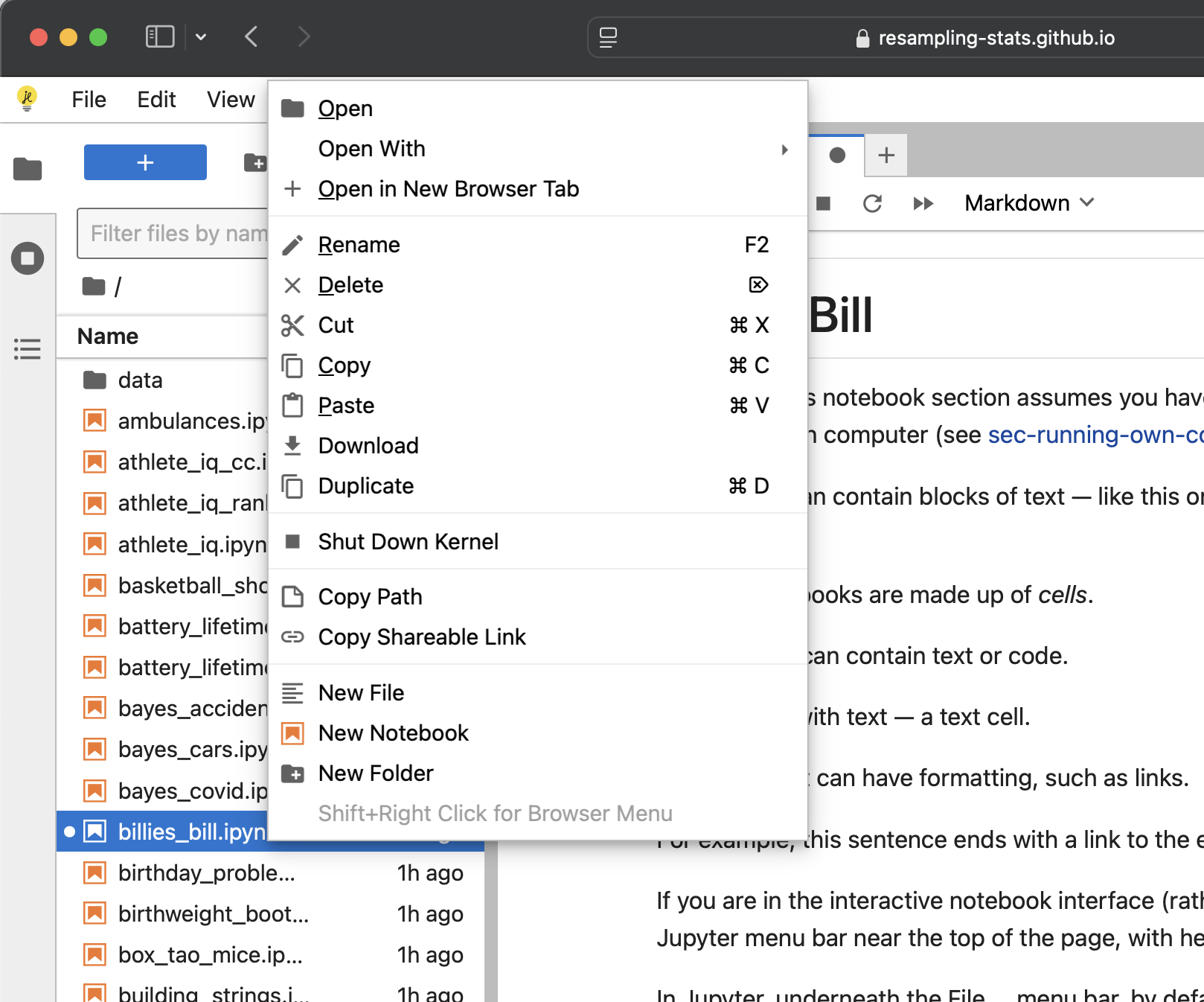

If you are running this notebook via the “Interact” button, you are running it using the JupyterLite system. JupyterLite keeps all its notebooks in your browser cache. This is a private and temporary store that the browser keeps somewhere on your system. This can be a problem if you find yourself clearing your browser cache for some reason, or if you start using another browser, that has a different cache. If you want make sure you have a copy of any changes you make to notebooks you ran with the “Interact” JupyterLite system, you might want to save a copy of the notebook outside the browser cache. To do this, look the pane to the left of the notebook for the name of the notebook. This name of this particular notebook is “billies_bill”, and you will see the notebook file in the left pane listed as billies_bill.ipynb. If you want to save a copy to your computer, first use the “File” menu, and the “Save” option, to save your notebook. This saves the notebook to your browser’s private store (the cache). Next right-click on billies_bill.ipynb in the left pane (see Figure 4.1), and choose “Download”. Save the file somewhere memorable on your computer. You can go back to the notebook by following the instructions at Section 4.9.

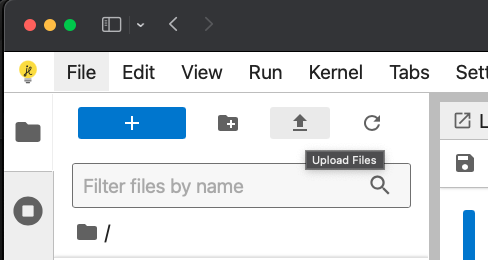

You can use this copy by re-uploading it to the “Interact” JupyterLite system. Go to the upload button near the top-left of the JupyterLite interface (see Figure 4.2). Select the .ipynb (Jupyter notebook) file you want to upload; once done, you can open the notebook using the file listing panel to the left of the interface.

billies_bill starts at Note 4.1.

Many people, including your humble authors, like to be able to run code examples on their own computers. This section explains how you can set up to run the notebooks on your own computer.

Once you have done this setup, you can use the “download” link that you will see for each notebook, to download the notebook to your machine. From there, you can open the notebook on RStudio.

Most of the download links in this book will trigger a download of the notebook file. This is a file with extension .Rmd, that you can open with RStudio.

Later in the book, you will see examples where the notebook loads a data file. In that case, the download link for the notebook points to a .zip file containing the notebook and the data file. Unzip the .zip file to get the notebook and data file, and then open the resulting notebook in RStudio.

You can run any of the code notebooks in this textbook on your own machine by downloading the notebook, via the download link at the top of each notebook section, and then opening the resulting notebook in RStudio.

Notice that the notebooks for download are in the same .ipynb (Jupyter) format as the notebooks in the “Interact” system (see Section 4.8). That means you can upload the .ipynb files from the download links into the Interact system and work with them there, and conversely, you can download the .ipynb files from the Interact system and work with them in Jupyter.

.Rmd) formatYou will notice that the notebooks for download are in the .Rmd (RMarkdown) format, rather than the .ipynb (Jupyter) format. RMarkdown is the standard format for notebooks in RStudio. The .ipynb format is the standard format for Jupyter. As you remember, the “Interact” system uses Jupyter, and you may have noticed that the notebooks there are in .ipynb. However, we designed the notebooks for download to work easily with RStudio — the system we recommend for running on your own computer, outside the browser.

At the moment, by default, RStudio will not open Jupyter .ipynb files as notebooks, and the “Interact” system will not open RMarkdown .Rmd files as notebooks, so treat these two systems as separate. If you download an .Rmd, do not upload it to the “Interact” system. If you download an .ipynb file, do not try and open it in RStudio.

In fact, it is relatively easy to convert between these two common notebook formats, with various methods, but we will leave you to explore that task if you are interested.

We are use a version of the Jupyter notebook for our interactive (web) examples. Although you can use the Jupyter notebook on your own computer, we recommend you use the RStudio desktop application.3 It works in similar way to Jupyter, but with some variation. You will find many good tutorials for RStudio online; at time of writing this DataCamp tutorial was a good place to start.

As you will read on the RStudio download page, linked above, you will need two software packages on your computer to run RStudio. These are:

The base R language gives you the software to run R code and show results. You can use the base R language on its own, but RStudio gives you a richer interface to interact with the R language, including the ability to open, edit and run R notebooks, like the notebook in this chapter. RStudio uses the base R language to run R code from the notebook, and show the results.

Install the base R language by going to the main R website at https://www.r-project.org, following the links to the package for your system (Windows, Mac, or Linux), and install according to the instructions on the website.

Then install the RStudio interface by going to the RStudio download page at https://posit.co/download/rstudio-desktop/, and navigating to the link to download RStudio Desktop. RStudio is an Integrated Development Environment for R. The RStudio IDE makes it easier to interact with, and develop, R code. You only need the free (default) version; it has all the features you will need. The free version is the only version that we, your humble authors, have used for this book, and for all our own work and teaching.

See Section 4.9.2 for a starter tutorial on running notebooks in RStudio.

Click the Download link below to download this notebook to your computer.

Notice that the Download link gave you a file ending in .Rmd, where “Rmd” is short for RMarkdown. RMarkdown is the name of the notebook format — and it is the native notebook format for RStudio. The .Rmd file is an RMarkdown version of the notebook.

Open the bill_in_rstudio.Rmd file in RStudio.

RStudio’s idea of a notebook is very similar to Jupyter’s — and this is not a coincidence, the Jupyter notebook was already popular when RStudio came up with its own take on this idea.

However, there are some differences between Jupyter and RStudio in the way that they think about notebooks, and in the notebook interface.

To start with the interface, notice that RStudio has its own menu, with “File”, “Edit”, etc. Each notebook has its own tab in the interface. If you have just opened this notebook, and no others, you will only have one tab, corresponding to this notebook. Depending on your configuration, you may also have other windows inside the RStudio window, for example, showing the variables defined in R, and the files in the same directory as the notebook.

Identify the notebook tab — the tab containing this file. You will notice that the notebook tab has a notebook toolbar at the top. We will come to that soon.

We have started with the interface, but now we return to RStudio’s slightly different concept of a notebook, compared to Jupyter.

For example, Jupyter thinks in terms of cells. All content in a Jupyter notebook has a containing cell; text cells contain text, and code cells contain code. In a Jupyter notebook, this text would be inside a text cell.

RStudio notebook thinks of the notebook differently. It conceives of the notebook as being text, by default. Within the text, there may be code chunks. These are the equivalent of Jupyter’s code cells — they are blocks of code you can execute within the notebook. The notebook interface displays any output from the code, including plots.

For example, the following is a code chunk (in RMarkdown terms):

# The cost of Alex's meal.

# alex_meal gets the value 10.50

alex_meal <- 10.50

# Display the cost of Alex's meal.

alex_meal[1] 10.5Now we return to the interface. Click inside the code chunk above. Notice that the code chunk is grey, compared to the usual default white for the rest of the notebook. At the top left of the code chunk, you will see a play icon. Click this to run the code and see the results.

There are various other ways of running code chunks. For example, the notebook toolbar that you identified about has icons that allow you run the code. In particular, there is a “Run” icon that triggers a drop-down menu, with options for running this and other code chunks. You will soon find yourself wanting the keyboard shortcuts to run code-chunks — please do start using these as early as you can — you will find they make you much more efficient and fluent in using notebooks in RStudio. To see the shortcuts, find the main RStudio menu, and select “Keyboard Shortcuts Help” for more information.

We will leave you with this brief introduction, and point you out to the interwebs to search for good tutorials on using RStudio. Books go out of date quickly, so we won’t risk instant obsolescence by recommending particular pages or videos here.

bill_in_rstudio starts at Note 4.4.

4.4 Comments

Unlike a calculator, we can also put notes next to our calculations, to remind us what they are for. One way of doing this is to use a “comment”. You have already seen comments in the previous chapter.

A comment is some text that the computer will ignore. In R, you can make a comment by starting a line with the

#(hash) character. For example, the next cell is a code cell, but when you run it, it does not show any result. That is because the computer sees the#at the beginning of the line, and then ignores the rest.Many of the code cells you see will have comments in them, to explain what the code is doing.

Practice writing comments for your own code. It is a very good habit to get into. You will find that experienced programmers write many comments on their code. They do not do this to show off, but because they have a lot of experience in reading code, and they know that comments make code easier to read and understand.